Will gold zoom higher with Greece on the brink of default? Or will it crash as the Fed pursues an “exit?” Why has gold not rallied with the recent retreat of the dollar? To understand where gold may be heading, keep in mind that this shiny metal isn’t changing; it’s the world around it that is. We contemplate why investors may want to hold gold as part of their portfolio.

In today’s world where the utterance of a pundit may move markets, it may be helpful to go back to basics to allow investors to make up their own mind as to what drives markets and what may be a good investment. As such, gold is simply a precious metal, a rare, naturally occurring chemical element that tends to be less reactive than most elements. These attributes have allowed gold to be the preferred choice as money:

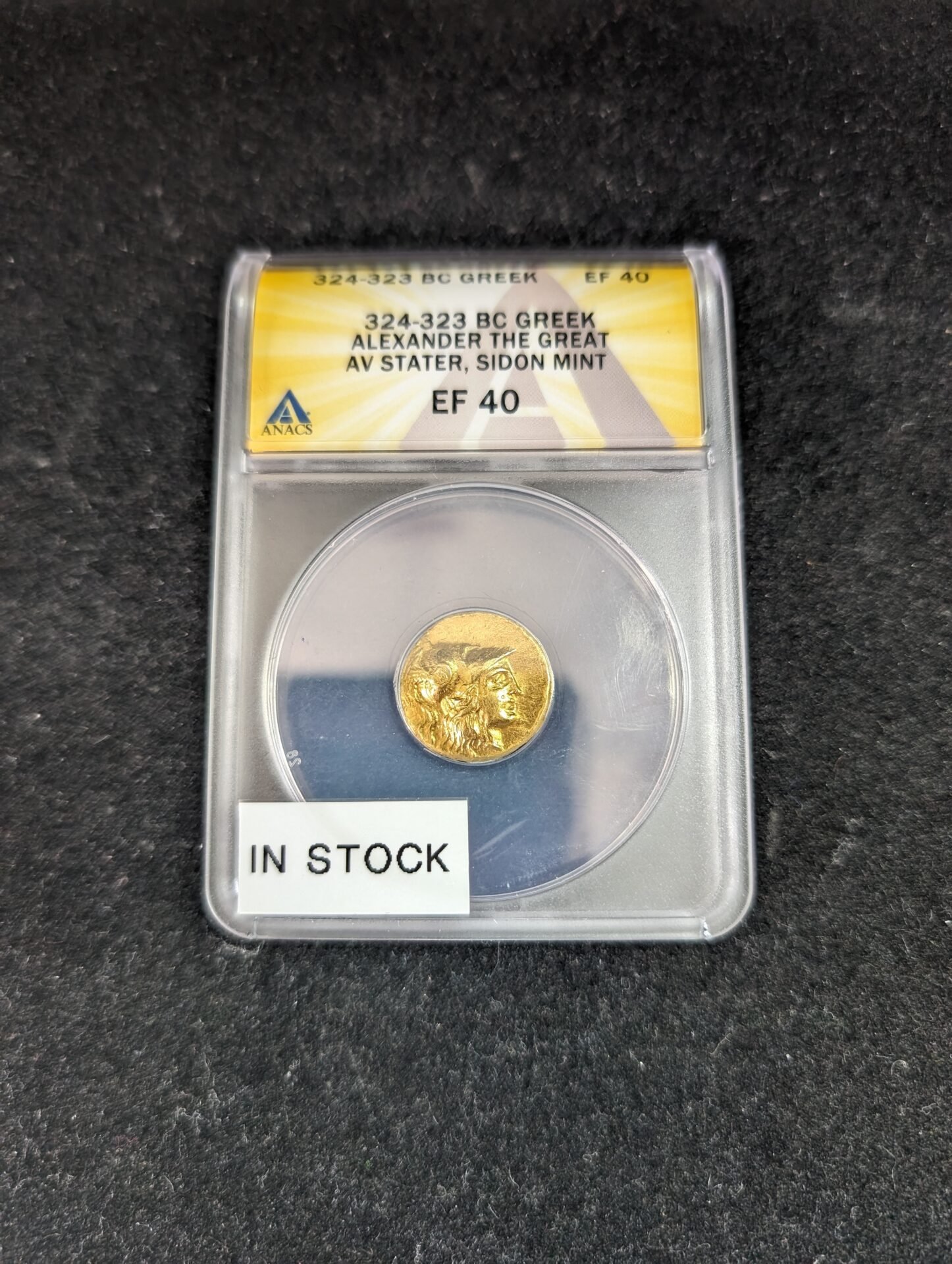

- Gold’s chemical characteristics make it a formidable store of value because it doesn’t change, doesn’t deteriorate over time. More so, because gold is rare, a lot of value can be stored in a small space: A “London Bar” – to the layman only known from James Bond or other movies, weighs about 400 troy ounces and is worth about half a million dollars.

- And gold is fungible and can be broken down into smaller pieces, such as minted into coins or smaller bars. As such, gold is suitable as a medium of exchange.

With the advent of fiat currency, many have said gold’s golden days are over because it is more cost effective to electronically wire money across the globe than to ship gold. There is also an electronic market for gold, although it is dominated by institutions with only a few firms offering consumers the ability to exchange gold electronically.

Naturally, many buying gold tend to do so because of its characteristics as a store of value. Mind you, some critics object that gold is a store of value given that the price of gold dropped from over $800 an ounce in 1980 to almost $250 in 1999 and 2001. When it comes to purchasing power preservation over long periods, however, gold has shown to preserve its purchasing power, as, for example, a gallon of milk cost about the same in gold 100 years ago as it does today; or, to use a frequently cited example, the same applies to a tailored suit. Conversely, when it comes to the U.S. dollar, we know its purchasing power has been eroding:

Indeed, we are concerned many currencies, not just the U.S. dollar, are at risk of losing their store of value.

A key reason why cash is not good at preserving purchasing power is the government issuing it has lots of debt: a government in debt has an incentive to debase the purchasing power of its currency. This isn’t just a criticism of the U.S. government, but governments in general. What’s different about gold is that governments can’t “print” it.

Many agree that cash might not be good at preserving purchasing power, but that one should be investing in productive companies instead, but was that a good idea in 1929 or 2000? Severe declines followed those stock market peaks. Someone arguing that regardless of those painful periods of stock market declines, stocks are a good long-term investment; many refer to such a person as a prudent long-term investor. Another person making the argument gold has fared well in the long-run is shrugged off as a gold bug.

Talking about prudent investors, most investment advisers don’t advocate putting all of one’s money into the stock market. Instead, they preach diversification. Except that, I would argue, textbook diversification may not work in an environment where most asset prices might be elevated. Central banks around the world, in our analysis, have compressed risk premia, meaning risky assets don’t appear particularly risky anymore, as evidenced by low volatility in the equity markets or low yields in the junk bond market. I hear stories about shifting from one sector in the equity market to another, as that other sector may perform better in a rising rates environment. That may well be, but if both equities and bonds were to plunge, is it sufficient consolidation to lose less money by being slightly better positioned?

What about an environment where:

- stocks may be expensive;

- bonds may be expensive;

- cash may not be safe in the sense that purchasing power is at risk.

In this context, we believe gold is worthy of being considered, even if it is not “productive.” In fact, it may be worth considering precisely because it is not productive, because gold just is. It’s the world around gold that changes, not the gold itself. As such, yes, the price of gold will vary. It’s part of the reason why gold has been cited as both an inflation and deflation hedge: in an inflationary environment, the value of cash versus gold may decline; in a deflationary environment, asset prices in general may decline versus gold (notably if there are defaults). So let’s look at the price of gold since 1970:

As the chart above shows, the price of gold clearly does not always go up. When all is said and done, however, the annualized return from 1970 until the end of March this year was 8.2% per annum, while exhibiting a correlation to equities of zero.

The zero correlation to equities is nothing short of stunning. We have all experienced the price of gold move together or in opposite direction with the stock market on certain days. But that they amount to a net zero correlation is quite amazing. The reason this is so special is that the two key elements investors may want to be looking for when considering to add to their portfolio is:

- Whether the return stream generated has a low correlation to other assets in the portfolio; and

- Whether there is an expectation of a positive return.

If both of these conditions are met, one can start discussing how much to add to a portfolio.

With regard to correlation, we think gold is a candidate investors may want to consider, especially in an environment where many other asset classes are highly correlated. An important reason for this low correlation may be the low industrial use of gold. While jewelry demand may give gold a bit of cyclicality, the low general industrial use may be a key driver why the price of gold has such a low correlation to stocks and many other asset classes.

What about the other aspect: positive returns. How is it possible that gold, this piece of metal that’s not productive, that it has had its price increase by an average of over 8% per annum? The results for long periods tends to outstrip inflation. There may be many drivers, but the simplest answer may well be that published inflation numbers under-state actual inflation. Other possible answers include increased demand (partially due to global population growth, if nothing else) while increasing supply isn’t that easy. In some ways, this may be irrelevant, because the real question is what will happen to the price of gold going forward.

What is intriguing about gold is that many acknowledge gold has been a good investment in the past, but going forward, they don’t think it’s going to rise in value. And that’s where we can finally turn to the current environment.

The reason I’m a bit skeptical about Greece driving gold higher is because I don’t think Greece drives the markets all that much these days. With many warnings about a Greek default one would think that the market has had time to prepare for it. Outside of Greece, the fear of “contagion” as a result of Greek default is limited these days because financial institutions have had years to prepare for a Greek default. Much of Greek debt is now held by the International Monetary Fund (IMF); as well as the European Central Bank (ECB) and European Union. In our assessment, losses on Greek debt won’t wreck the financial system, likely not even any financial institution, as losses have been “socialized.” This socialization of losses is foremost a political problem. I don’t rule out that the price of gold may be affected, but it may be difficult to devise a profitable gold investment strategy purely based on Greece. A longer-term strategy buying gold in anticipation that more debt might be monetized may be more worth considering. Although we think this belongs in the long-term bucket, a similar bucket as is required for dealing with long-term entitlement issues in the U.S.

To me, the below chart is one of the most compelling arguments why, going forward, gold may be no worse an investment than in the past. We don’t know where the price of gold is going to be tomorrow, but we have made promises in the U.S., just as in much of the developed world – that may be difficult to keep. The temptation to debase the purchasing power of the debt is great.

Notably, even as rates may be moving higher in the U.S., will real interest rates, i.e. rates after inflation, be positive? The last paragraph published by the Fed’s FOMC has now included many times what we interpret to be all but a promise to be late in raising rates: “The Committee currently anticipates that, even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below levels the Committee views as normal in the longer run.”

In plain English, we believe the Fed will be behind the curve. Bill Gross calls for a “new normal” that may see interest rates top out at 2%. Our question is: where will inflation be if interest rates top out?

I have discussed this view that we may not see positive real interest rates for an extended period over the next decade with some policy makers. A response I received from a Fed official was that this view is unlikely correct because it wouldn’t create a stable equilibrium. My response to that was that I never said this would be stable

Axel Merk

Manager of the Merk Hard

Asian and Absolute Return Currency Funds

www.merkfunds.com